Spotlight On Diversity: Lucknow

Situated on the banks of River Gomti, Lucknow (erstwhile capital of the Kingdom of Awadh) remains one of the most sophisticated and preserved cultures of the Indian subcontinent.

Lucknow is more than a city, it is a culture that conjures a symphony of words and senses – tehzeeb and takalluf, shayariand shorba, nihari and chikankari, poetry and prose, thumris and ghungroos. It is a genteel fusion of Hindu and Islamic cultural nuances with its buttery Lucknowi language, extraordinary history, awe inspiring monuments, resplendent textiles and heavenly cuisine. The immaculate mannerism of ‘pehley aap’ (after you) captures the spirit of Lucknow.

As part of our initiative ‘Spotlight on Diversity’, Rashmi Singh, Partner Designate, recently illuminated members of the Firm on the rich culture and heritage of the city of Lucknow – we present glimpses of her presentation below:

Monuments

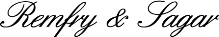

Lucknow’s magnificent architectural marvels have earned it the sobriquet ‘Constantinople of East’. The monuments are mix of indigenous Awadhi design mixed with Turkish, Irani and other influences.

If you travel to Lucknow by rail you will alight at the Charbagh Railway station, which in itself is a major tourist attraction. Called Char Bagh (four gardens) because of the four gardens which are believed to have existed here till 1867 (only one garden remains now), when viewed aerially, it resembles a chess board, with the domes, pillars and turrets appearing like chess pieces on a board. It is also believed that if you stand on the porch of the station, you will not hear the noise of incoming and outgoing trains. This is also the place where Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, two people who defined the national freedom movement, met for the first time in 1916 in the backdrop of the 31st session of the Indian Congress.

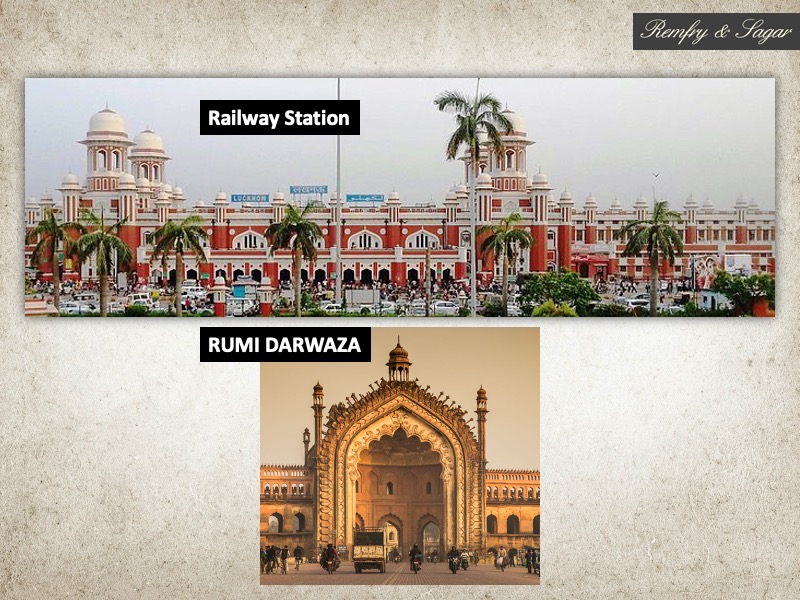

Rumi Darwaza, also known as the Turkish Gate, is an imposing gateway built by Nawab Asaf-Ud-Daula. It stands sixty feet tall and was modeled after the Imperial Gate (Bab-I Hümayun) of the Topkapi palace in Istanbul. The Rumi Darwaza leads into the courtyard of the Bada Imambara. Interestingly, both monuments were build by the Nawab when an unprecredented famine struck the region in 1784. He undertook construction under a food for work programme for the masses which minted a famous saying in Awadh – “jise na de maula use de asaf ud daula”. The best architects of the time were commissioned to design a grand prayer hall for the city of Lucknow, the capital of Awadh, and more than 20,000 men were employed for the construction of the complex. Legend has it that the ordinary citizens worked all day to bring up the magnificent edifice; the elite, meanwhile, were made to bring down all of it during the night (which both anonymity and employment to the unskilled aristocrats) – it was the Nawab’s way of making sure that no one was ever out of work. Today, the Bara Imambara is known its celebrations of Muharram and also a Bhool Bhulaiya – a labyrinth of interconnected passages and doors; it is said that there are 1024 ways to reach the terrace but only two to come back.

There is also a Chota Imambara – one of its halls displays chandeliers brought from Belgium. Then there is the Residency – a set of buildings that are enclosed in a large compound – which served as the residence for the British Resident General who was a representative in the court of the Nawab. History also remembers it as a hideout for the British families during the First War of Indian Independence in 1857 (or the Mutiny, as some call it).

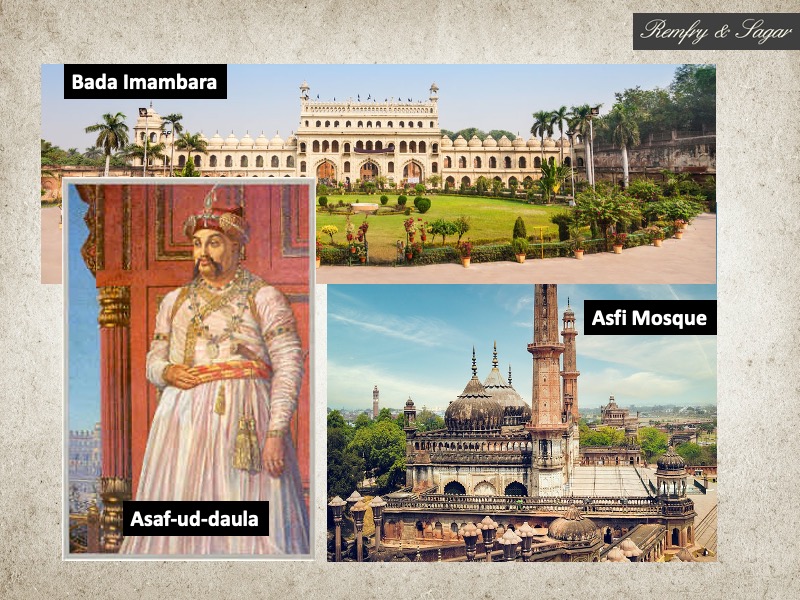

In the late 1700’s was also built – La Martiniere – a country home of Major General Claude Martin – which was turned into a boy’s school in 1845. A fine example of the French style of architecture – it was the scene of a great deal of action during the First War of Indian Independence in 1857. In 1935, the school was awarded battle honours for its role in the defence of Lucknow in 1857, the only school to have been so honoured (the only other is the McGill University in Canada for its role in the Great War). Restoration work is ongoing at this fabulous building – revealing plastered over elements, bricked up fireplaces and wonderful new stories of times gone by!

Dance

Kathak, one of the major forms of Indian classical dance, is traditionally attributed to the traveling bards in ancient northern India known as Kathakars or storytellers (Katha means “story”, and Kathakar which means “the one who tells a story”). It evolved into a formal dance form between 15 BC and 10 BC and the next important phase in the evolution of Kathak was during the 15th century Bhakti Movement which swept over India. The stories of Radha and Krishna are a strong element in Kathak. Interestingly, Kathak performances also include Urdu Ghazals and commonly used instruments brought during the Mughal period. As a result, it is the only Indian classical dance form to feature Persian elements.

Kathak is found in three distinct forms, called “gharanas”, named after the cities where the Kathak dance tradition evolved – Jaipur, Banaras and Lucknow. While the Jaipur gharana focuses more on the foot movements, the Banaras and Lucknow gharanas focus more on facial expressions and graceful hand movements. Lucknow was home to one of the most famous exponents of kathak in recent times – Pandit Birju Maharaj – who passed away in early 2022.

Song

Thumri is North India’s most popular light-classical song form, developed during the 19th century at the court of Lucknow’s ruler Wajid Ali Shah. It has very strong associations with kathak, of which the Shah was also a leading exponent. Given this connection between music and dance, thumri rapidly became the mainstay of courtesans.

Unlike the purely classical forms of Dhrupad and khayal, thumris tend to be strongly text-led with words playing a more important part than music. In general, where Indian music is concerned, the more audible the words the less classical the musical form.

In later years, Begum Akhtar (1917-74) the queen of Lukhnawi thumri and ghazals, told the world the sweetness and the diverse combination that Lakhnawi singing could have. Her singing always created visions of the glorious and opulent era when high-class music, Urdu poetry, refined tastes, gracious living, polished manners and polite language in everyday life, had all combined to make Lucknowi culture famous and widely admired.

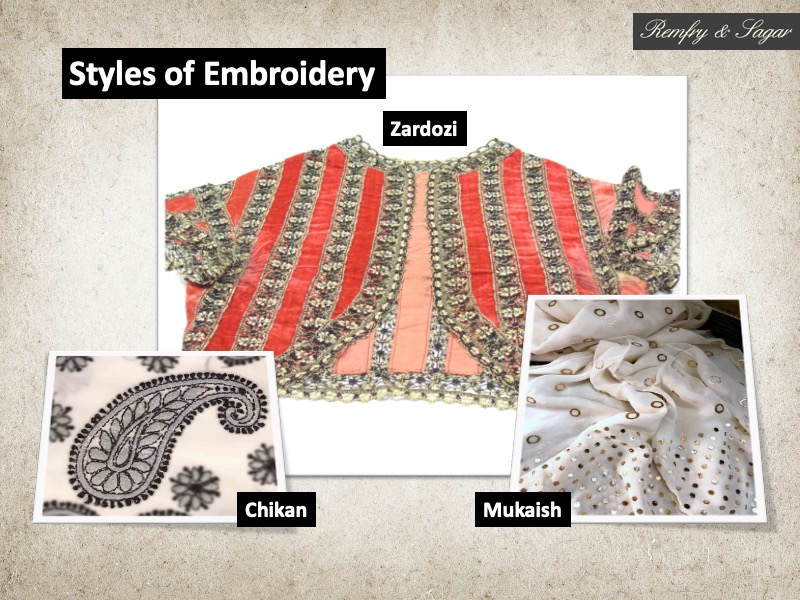

Embroidery

Zardozi is form of embroidery that came to India from Persia. Its literal translation, “zar” meaning gold and “dozi” meaning embroidery, refers to the process of using metallic-bound threads to sew embellishment on to various fabrics. This heavy and intricate style of design is said to have been brought to India with the Mughal conquerors. The Geographical Indication Registry has accorded all Zardosi textiles manufactured in Lucknow and its surrounding districts with the GI tag.

Mukaish embroidery involves twisting thin metallic threads to create patterns all over the fabric – most commonly patterns featuring dots. This form of embroidery was first developed for the Lucknow royalty since Mukaish work initially used precious metals like gold and silver to make threads.

Chikankari is a delicate and artfully done hand embroidery on a variety of textile fabrics like muslin, silk, chiffon, organza, net, etc. White thread is embroidered on cool, pastel shades of light muslin and cotton garments and this too is registered as a Geographical Indication in India.

Cuisine

Food in Lucknow, is a sensory experience that every foodie deserves. Mutton dishes such as Kebabs, Biryani and Nihari and the desserts of the city are deeply embedded in the history of this city and now define the culinary experience of the place.

Tunday Kabab: Tunda literally means “a person with a hand disability”. Tunday Kebabi was set up in the Chowk market in 1905 by Haji Murad Ali who lost his arm after falling from the terrace while flying a kite, thereby earning the said nickname. His specialty was the Galauti kebabs. The now 110-year-old shop still sells them to the keenly waiting locals.

There is more to Galauti kebabs – as age caught up with Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula, he began to lose teeth. His palette, however, was too used to the taste of Kebabs. Therefore, he declared royal patronage to whoever could craft a special Kebab that did not require chewing.

Thus was born the Galauti-kebab by Haji Murad Ali (or Tunday ke Kebab) and kebabs took a turn from being coarse and chewy to melt in the mouth ones bursting with flavour. More than 160 spices are rumoured to be mixed in the meat before it is made into a paste and cooked. Other popular kebab varieties include Kakori-kebabs, Shammi-kebabs and Seekh-kebabs.

Biryani: This divine dish is prepared using juicy pieces of marinated mutton or chicken and long-grained rice. Both are cooked separately for some time and then layered together and cooked in Dum fashion. The meat becomes succulent and falls off the bone with the slightest touch. The long grains of the rice grab on to the aroma of the spices and perfectly compliment the meat. Awadhi-Biryani is uniquely cooked with large amounts of ghee or clarified butter and uses khade or whole spices. It is characterized by an earthy delicate flavor and a strong mouth-watering aroma which makes it hard to resist.

Malai Paan: A Lucknawi meal is incomplete without the city’s famous Paan called Malai-paan or Balai-ki-gilori from the 1800s! Instead of the normal betel leaf Paan found in the rest of the country, this special Paan uses Malai as a cover for the ingredients. Malai, a type of clotted cream, is beaten till it becomes paper-thin and then stuffed with various dried fruits, sugar crystals (Mishri) and rose water. All this is finally wrapped in real edible silver. The story of the origin of this delicacy is just as rich as its taste. It was made for the Nawab of Lucknow when he was asked to reduce his tobacco intake due to medical reasons. Now, due to blossoming street food culture, locals can enjoy this delicacy throughout the year.

Language

Language has always been of utmost importance to Lucknow. Urdu and that too Lucknowi Urdu is a natural part of day to day conversation of the people of Lucknow, irrespective of their mother-tongue or religion.

A story of the great Urdu poet Mir Taqi Mir well illustrates the importance and refinement of Lucknow’s Urdu. Mir Taqi Mir was once returning from Delhi to Lucknow and a gentleman from Delhi offered to give him a lift in his tonga. The man talked incessantly during the journey but Mir remained silent. When he reached Lucknow, Mir profusely thanked that man for giving him a lift and gifted whatever money he got from the Mushaira in Delhi. The man then asked him, “Mir Sahab why didn’t you utter a single word during the whole journey?”. “Because I didn’t want to sully my language by replying to your questions couched in an inferior tongue,” replied Mir Taqi Mir calmly.